Brian McGrath

This essay briefly reflects on the period in the 1980s between two of my academic encounters with Susana Torre. The first took place in 1979, when I was a student, at the beginning of her teaching career; and the second, in 1991, as a new faculty member, when Torre became the first chair of the Department of Architecture at Parsons School of Design. This personal perspective is formed within a specific window into an important generational shift in architectural education. I was born at the tail end of the baby boom, caught between the ideals of the ’60s boomers and the realities of the neoliberal world order introduced at the end of the 1970s. My age group directly experienced the cognitive dissonance that resulted from the abrupt shift to a return to “autonomy” of the discipline of architecture from the progressive social and environmental concerns brought to the academy since the ’60s. Torre served as an effective bridge over this paradigmatic chasm, as she taught and practiced the integration of architectural design and progressive social change, a message crucial for the restoration of the ethics by Generation X.

January, 1979

During the winter break of 1979, five classmates and I traveled to midtown Manhattan before our final semester of the Bachelor of Architecture program at Syracuse University. Our goal was to convince Susana Torre, who would be a visiting critic assigned to a third-year studio at Syracuse that semester, to take us on as well. I don’t remember having any socially progressive motivation to seek out design instruction from the only women in five years of architectural design studios. But for all of us, in a holding pattern at Syracuse ready to enter the professional world of New York, a successful young architect in Manhattan seemed like a viable stepping stone. I had recently completed a semester at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies on West Fortieth Street and was not ready to go back to the old school. The visit only strengthened our resolve to work with Torre as we talked to in her studio facing the MoMA garden.

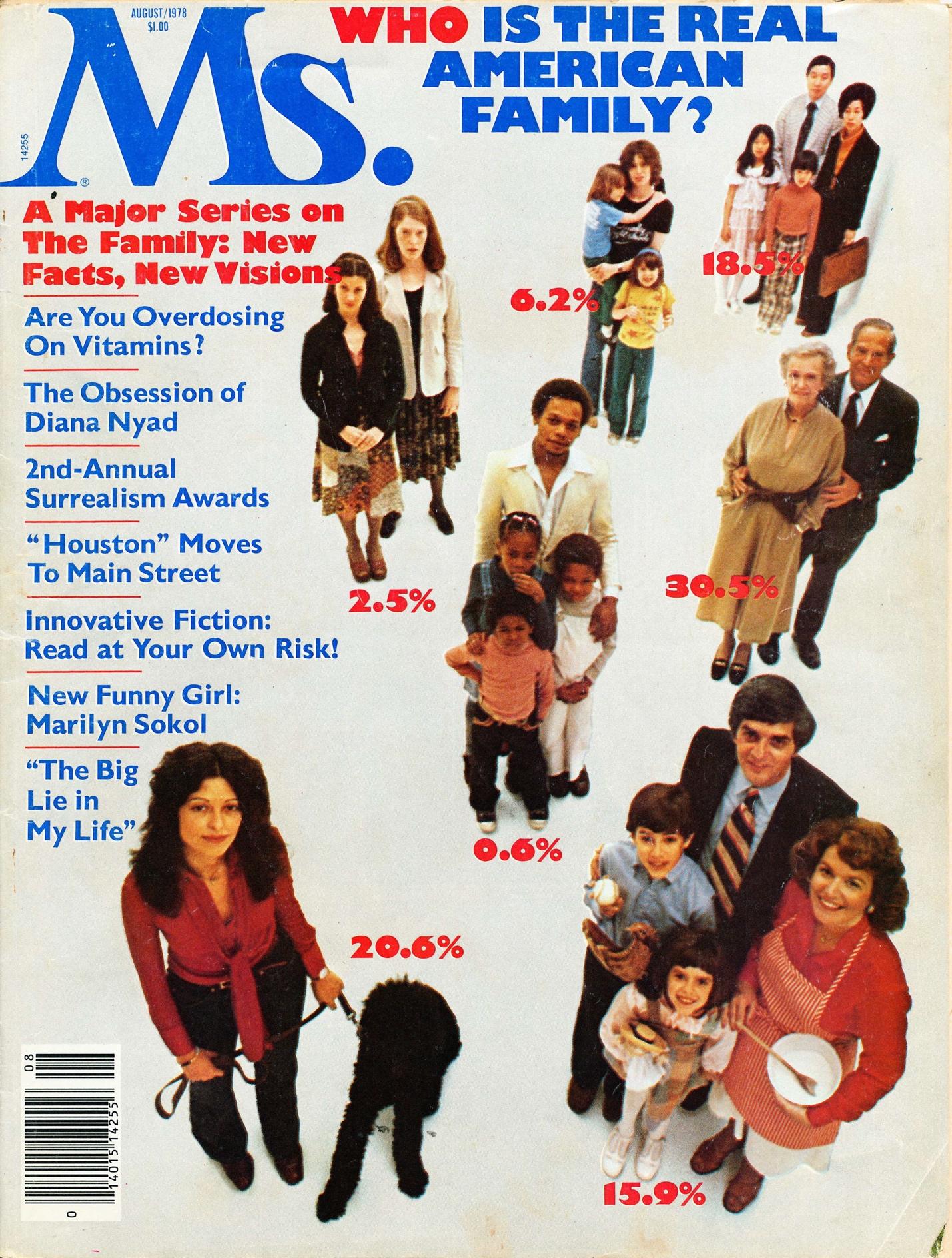

With Dean Werner Seligman’s consent, the studio was quickly reconfigured into a vertical format where teams of third- and fifth-year students worked on a complex housing program for a large vacant lot in downtown Syracuse, with a distinctly feminist twist. Torre’s brief for the studio was largely drawn from an August 1978 special issue of Ms. magazine, entitled “Who is the Real American Family?” The cover dramatically unmasked the myth of the American family by showing that the working dad/stay-at-home mom structure applied to only 16 percent of families in the United States. The studio integrated three aspects of feminist thought into a complex architectural design problem: a women-centered focus on labor and space, a critique of the American suburb, and a feminist focus on domesticity.

The studio program began with a description of an employed woman’s day in 1979: raising the family in the morning and setting them out for the day; balancing a professional job with shuttling kids, food shopping and preparing meals, and getting everyone to bed. Torre’s brief connected this problem to the design of American suburbs and housing and the dichotomy between public and private, paid and unpaid, arising from structural spatial and economic separations. The only other solutions offered in the neoliberal economy are private, commercial, for-profit childcare, homecare, food, and transportation services. The rise of fast food and commercial day care and their low-paying jobs are complicit with this regime. How do these workers, in fact, take care of their own children?

The studio proposed the design of an experimental residential center that was based in the remaining low-interest Housing and Urban Development cooperative loan programs available at that time. The site was two large vacant blocks in an urban renewal area along an elevated interstate highway separating the university from downtown Syracuse. The studio also analyzed experimental social housing of the past, such as Karl Marx Hof in Vienna, where architectural design and economic organization transcend old descriptions of the home. The program specified a great variety of housing types, reflecting not only the family diversity in the Ms. magazine cover story but also shared amenities, as well as income and job-generating services such as day care, laundry, cooking and dining, co-op food store, elderly services, and public and private outdoor space. The topic was not just an academic exercise, as at the time, Architectural Record held a roundtable on the issue and published an article on the student projects.

In addition to the Marxist-inflected focus on labor and the political economy, the design studio also incorporated a remarkable experiment in architectural space. As Torre would later publish in Heresies Issue 11, Making Room: Women in Architecture, (Vol 3 No 3, 1981), her proposition was “Space as Matrix”. She argued that both Victorian spatial arrangement of enclosed rooms and corridors and modernist open plan were inadequate for contemporary life. The architectural design of an experimental residential center focused on flexible and complex room arrangements, connections between indoor and outdoor spaces; open kitchens, laundry, and play areas, as well as cooperative cooking and homework. “Space as Matrix” proposes breaking down the conventions of public and private in favor of spatial continuity, hierarchy, and multi-functionality in order to accommodate changing and temporary patterns. Remaking the closed kitchen into a common shared space was central to the interior aspect of the program.

The Ms. Magazine cover for August 1978 provided inspiration for the spring 1979 architectural design studio taught by Susana Torre at Syracuse University. The program called for not only a greater variety of spatial variety in house units, but also shared space for day care, elderly care, common kitchens, and laundries.

1991

In 1991, Torre was appointed as the first chair of the new Department of Architecture at Parsons School of Design, and she invited me to join the faculty. A hundred-year-old art and design college, Parsons became part of The New School for Social Research in 1970, at a time when design education was being radically redefined toward more socially progressive goals. This was especially true of interior design at Parsons, which was renamed Environmental Design. There could have been no better choice to bring the progressive ideas to architectural education to Parsons and The New School than the leadership of Torre. Torre transformed the single-degree undergraduate program in environmental design, incorporating a professional Masters of Architecture degree and a BFA in Architectural Design, as well as reinstituting the BFA in Interior Design.

As a kind of rehearsal to the new architectural school at Parsons, Torre organized a major conference at The New School just before her appointment in association with Architects Designers and Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR). The conference, "Social Responsibility and the Design Professions” was provocatively subtitled, “A Forum to revive a long-silenced discourse and to re-engage the design professions in the processes of cultural and institutional change in America." Panels included Public Space and the Challenge of Cultural Diversity with Saskia Sassen, Janet Abu-Lughod, and Marshall Berman; Changes in Demography, Economics, and Communications and Their Impacts on Urban and building form, with Christine Boyer and Susan Siebert; urban development and the natural Environment with Robert Yaro and Diana Balmori; and Ethics and Aesthetics in the Discourse on Design with Zeynep Celik and Max Bond.

Torre asked me to develop analysis and representation courses and studios for both the undergraduate and new graduate students as well as develop a new course, Theory of Urban Form, to complement Peggy Deamer’s course, Theory of Architecture Form. The graduate analysis and representation courses covered two semesters that coordinated with the theory courses—one on building analysis and a second on urban analysis. In preparation for this teaching in August, 1991, Torre arranged for a young undergraduate student to give me a crash course on the beta version of a new 3D modeling software, formZ, in order to begin incorporating digital technology into the architectural curriculum.

In addition to the remarkable curricular innovations Torre brought to Parsons, she introduced a creative culture and public life to the school that put into action the social and spatial ideas already a part of her design studio program at Syracuse. Notable were the exhibitions, conferences, lectures, and school-wide charrettes, such as for the memorial for the uncovered African American Burial Ground in 1992. Notable was the commissioning of Allan Wexler’s Mobile Kitchen, located outside the departmental offices and connected to the design studios in the school’s cast iron loft building on Thirteenth Street. The kitchen folded into a useless nook behind the elevator, but unfolded for exhibitions, reviews and lecture events, temporarily transforming offices and studios into a home.

Caption: Torre commissioned Allan Wexler to design a portable kitchen that could be tucked away in leftover space beside the elevator on the second floor of 23 East 13th Street. The project brought some of the feminist goals of the architectural studio to an institutional setting and has been the social heart of the School of Constructed Environments for two decades.

My own rehearsal for teaching at Parsons included working at Jim Polshek’s office on Union Square and teaching at the New Jersey Institute of Technology in Newark. I settled into my new home in Alphabet City in Manhattan’s East Village in June 1981—the same month that the New York Stock Exchange changed from paper to electronic trading a decade before architecture education adopted the computer. The challenges of housing and urbanism that Torre presented in the undergraduate studio at Syracuse violently played out in my neighborhood. Over the course of that decade, I had numerous opportunities to work with Torre on urban design topics for the American city—always collaborative interdisciplinary teams, planners, landscape architecture, graphic designers, architects, urban designers. My neighborhood and teaching came together when ADPSR organized a design competition for Alphabet City in 1990 called Houses and Gardens on the Lower East Side: Can We Have Both?

The Lower East Side studio served as a template for the larger vision Torre had for making an activist architectural department—one that would engage in the housing and urban issues of our city. Janet Abu-Lughod’s longitudinal fieldwork in the East Village served as a foundation for Parsons to become a partner in the neighborhood’s future. The signature design studio for the new graduate program was a community design and housing project. Torre directed a partnership for the students to collaboratively design a mixed-needs institution that provided housing for low-income disabled people. The project sat on an irregular grouping of vacant lots facing Tenth and Eleventh Streets and Avenue C with Community Access, Inc. and included rental housing with studio and two-bedroom apartments, community laundry rooms, tenant meeting rooms, and offices for counselors. Sandro Marpillero and Silvia Smith from Fox and Fowle were the architects of record.

2018

Walking through Parsons School of Constructed Environment’s (SCE) new offices and studios on the twelfth floor of 2 West Thirteenth Street, one can experience the power of Torre’s “Space as Matrix” model. Designed by Rice+Lipka Architects, the SCE hub is a suite of open spaces and closed rooms with no wall impeding the 350-degree view over Fifth Avenue and Greenwich Village. A common kitchen is located between administrative and faculty offices and studios and lecture rooms. Torre’s legacy is also reflected in the growth of the student body and number of programs. SCE now includes undergraduate and graduate degrees in architecture, interior design, and lighting design, as well as in product and industrial design. It is also home to the country’s signature urban design-build program, the Design Workshop, which continues to serve in the graduate architecture program. Undergraduate students in the program annually construct a temporary outdoor public space as part of the city’s Street Seats program on the corner of Fifteenth Street and Fifth Avenue, a living room for a department that now occupies two buildings on either side of the intersection—as a reminder to New York, Parsons, and The New School of SCE’s feminist legacy.

Caption: The new twelfth-floor hub for the School of Constructed Environments at 2 West Thirteenth Street employs the architectural concept described in “Space as Matrix.” The design, by Rice+Lipka Architects, deftly balances semi-enclosed shared space for faculty and administrators, open studio space, private meeting and seminar rooms, and a common eat-in kitchen without blocking more than forty windows with views of Midtown and Lower Manhattan.

Brian McGrath’s books include: Urban Design Ecologies (2012), Resilience in Ecology and Urban Design (2012), Digital Modeling for Urban Design (2008), Cinemetrics (2007), and Transparent Cities (1994). He is a professor of urban design and a principle investigator in the Baltimore Ecosystem Study. He also served as a Fulbright Senior Scholar in Thailand, and an India China Institute Fellow.