"Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

-George Santayana

How we address our history affects how we remember it and frames the lessons we learn from the past. Racial violence is often glossed over in school, watered down in textbooks, and sanitized for white America’s convenience. Many Americans, however, are not privileged enough to be able to ignore this part of American history. Violence and terrorism have haunted black communities, particularly in the South, shaping race relations and power structures through policy and psychology.

All over the United States, organizations like the Ku Klux Klan targeted black Americans with beatings, bombings, lynchings, and other acts of terror to demonstrate their power and to repress the political and economic action and success of black communities. This violence intensified when the Confederacy was defeated in 1865 and continued with increased intensity until the murder of Emmett Till in 1955. It was only after the media coverage of Till’s open casket—a decision made by Till’s mother to display her fourteen-year-old son’s unrecognizably beaten face—that white Americans began to express outrage and call for justice.

MASS Design Group, and Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) created the Memorial for Peace and Justice to finally memorialize the lives lost through these acts of racial terrorism. MASS is a nonprofit architecture firm known for empowering communities through their thoughtful design and work with nonprofits. EJI has been working for twenty-nine years to end mass incarceration, protect the basic human rights of vulnerable communities, and end racial and economic injustice against these groups.

The Memorial for Peace and Justice is sited in Montgomery, Alabama, a city with a vital history in both the civil rights movement and the enslavement of African Americans. Pre-Civil War, Montgomery was one of the largest trading posts for domestically sold slaves. During the Civil Rights movement, it was also the city where Rosa Parks sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The Freedom Riders were attacked by a mob at the Montgomery Greyhound station in response to their fight to end illegal interstate segregation. John Lewis led an attempted 54-mile march from Selma to Montgomery, during which his marchers suffered police brutality on the Edmund Pettus Bridge so vicious that 50 protesters were hospitalized after being severely beaten. While the city had dozens of statues and memorials celebrating its Confederate heritage, it was not until 1990 that the city began to use signage and statues to acknowledge its role in the civil rights movement.

At the memorial entrance is a quote by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: “True peace is not merely the absence of tension; it is the presence of justice.” Passing through the gate, an outdoor path walks you through a brief history of the enslavement of Africans, their treacherous voyage to the Americas, emancipation, and the creation of Jim Crow laws. The pathway is lined with written history and accompanying sculptures depicting the physical and emotional struggles of African Americans leading up to Reconstruction.

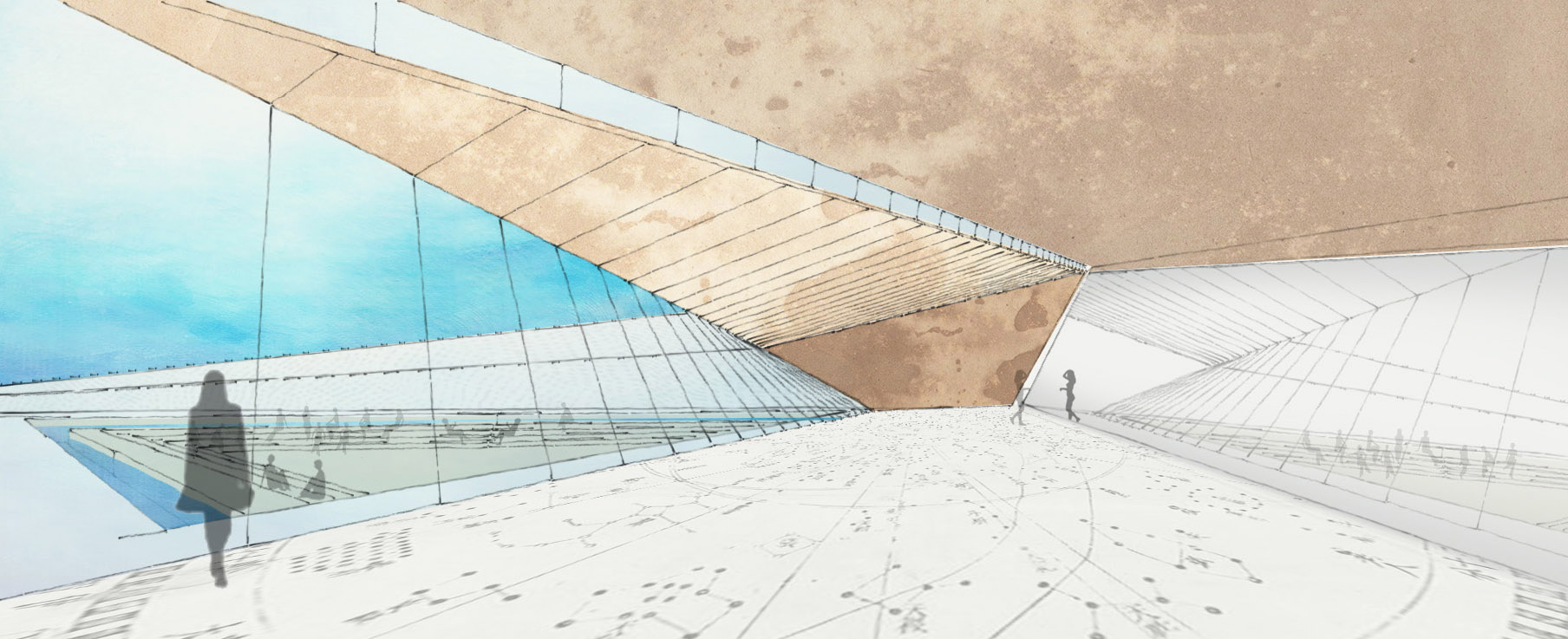

Approaching the central structure of the memorial, you enter the era of racial terror in America. A roof floats over the square pavilion, with a central courtyard open to the sky. As you circulate through the building, the path descends lower and lower. In the first section, corten steel boxes hang just above the floor. From afar I thought each box represented a single life lost, but to my horror I discovered every box represents a county—one for each county in the United States where a known lynching had taken place. On each box is a list of names that ranged in length. Some boxes contain dozens of names. If a person’s name was unknown, but their death had been recorded, they were listed as “unknown.”

As the path descends, the roof remains at the same level. By the second side of the pavilion, the boxes float above you. While it very literally represented the way many of these lynchings happened, through hangings, it also symbolized two things to me: the weight of the life lost and the feeling that the names where floating towards the sky, towards freedom.

In the third wing, the boxes hang about eight feet from the floor and as the viewer continues to descend, the boxes hang well above them, at about twelve feet. Along the walls are plaques detailing what triggered white Americans to lynch black citizens. People were lynched for reasons that included registering black voters, refusing to give up their land to white people, asking for a drink of water, complaining about the lynching of a husband, and eloping with a white woman.

The final wing focused on two sentences. The wall read, "Thousands of African Americans are unknown victims of racial terror lynchings whose deaths cannot be documented, many whose names will never be known. They are all honored here.” This wing leads you to the final pathway, which brings you through even more boxes; this is powerful because as you leave the structure you may assume that all of the boxes have been displayed, but there are many more names waiting to be read and acknowledged.

Beyond the final box is a statue of Rosa Parks in celebration of the civil rights victories of the 1950s and 1960s but beyond her, there is another reminder of how much we still must do for civil rights and racial equality. The final stop along the timeline of racial terrorism is a statue of a line of black men with their hands held above their heads, a reminder of the all-too-frequent killing of unarmed black men at the hands of the police, is the final stop along this timeline of racial terrorism. Although mass lynchings no longer take place, last year dozens of unarmed people of color were shot and killed by the police.

The monument forces the viewer to feel and acknowledge the weight of the history. While at times overwhelming, the structure itself was peaceful, calming even. I found myself sitting and thinking about what I had seen, and instead of feeling bogged down by the weight of the subject matter, I felt empowered. What holds many people back from visiting these memorials is the sadness and reflection they must face, but in order to effect change, we must recognize the past and our roles within it.

As a white woman from the Northeast, some may argue that I am not a directly impacted by this history; am I the right person to be reviewing this? People of all backgrounds need to experience this memorial. My experience was drastically different than that of a person whose family has been victims of these crimes, or a person whose family took part in the lynchings. Regardless of background, this memorial should mean something to you. It reminds me of the consequences of apathy and motivates me to engage in the fight against oppression. It reminds me of the innate privilege I have, and how others have suffered and continue to suffer in America due to lack of opportunity, lack of respect, and lack of understanding for those who come from diverse backgrounds. As an architecture student, my profession has been guilty of heinous racism and lack of empathy for underprivileged and diverse peoples. We can either practice through ignorance or thrive by elevating and empowering disenfranchised communities.

The Memorial for Peace and Justice screams for just that: peace and justice. While we may like to believe that this history is behind us, the Equal Justice Initiative reminds us that racial terror and inequality did not end, they just evolved. This memorial gives America a place to publicly express the pain and anguish this truth evokes. EJI also created the Museum of Legacy in Montgomery, which chronicles the evolution of slavery into the current system of mass incarceration.