Rosa Sheng, AIA & Annelise Pitts, AIA

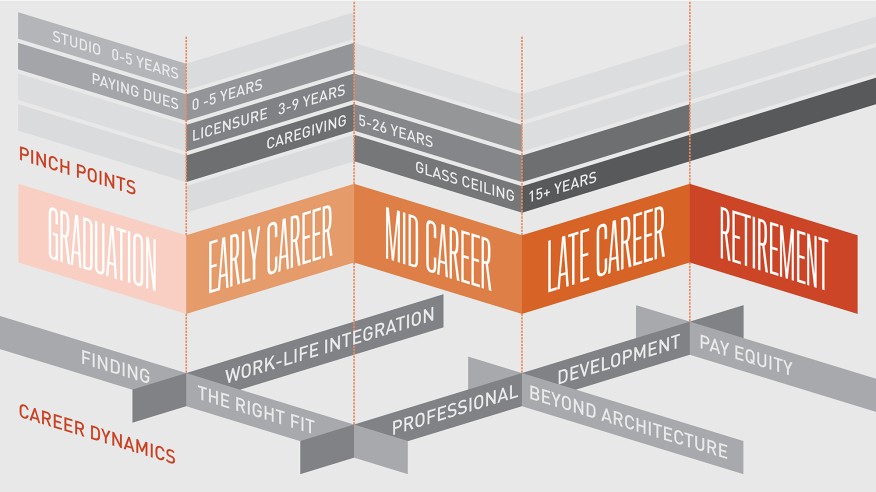

Findings from the AIA San Francisco’s Equity by Design (AIASF’s EQxD) committee 2016 Equity in Architecture Survey. Design by Atelier Cho Thompson. Courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee.

Why Equity Matters for Everyone

“Equity” and “equality” have long been used interchangeably, but the terms do not mean the same thing. While the focus of equality is framed with sameness being the end goal, equity may be defined as a state in which all people, regardless of their socioeconomic, racial, or ethnic grouping, have fair and just access to the resources and opportunities necessary to thrive. Beyond equity’s newer association with pluralism, it has long been connected to financial capital, as well as to collective ownership, vested interest, and a sense of value or self-worth.

Equity has strong potential as a new paradigm and social construct to succeed on multiple levels—equity in education, equitable practice in the workplace, and social equity in access to basic life resources, healthy and safe communities, and public space in our urban centers. The equity-focused value proposition at all these levels is rooted in transparency, education, collaboration, and trust.

The lack of equity in architectural practice and allied professions has made these fields prone to lose talent to other, more lucrative career paths due to multiple factors that challenge retention: long hours, low pay, lack of transparency for promotion, and work that is misaligned with professional goals. In order to have justice and equity in the built environment, the architecture, engineering, and construction design workforce needs not only diverse representation that reflects the rapidly changing demographics that we serve, but also diversity of thinking influenced by empathy and emotional and social intelligence. Often the public does not fully understand the value of what architects and allied professionals bring to the table in terms of the social impact of design that can inform equitable, just, and sustainable public and private spaces.

Origins: The Missing 32 Percent

In the United States, women represent slightly less than 50 percent of the students graduating from accredited architecture programs. The percentage of women who are American Institute of Architects members, licensed architects, and senior leaders varies between 15 to 18 percent of the total. While the exact percentages are in constant flux, the challenge of losing a large pool of architectural talent remains the constant. Statistics released by the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, “Where are the women in Architecture,” coupled with the momentum behind the Denise Scott Brown Pritzker Prize Petition, The He for She campaign by the United Nations, Lean In by Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, and similar conversations about solidarity against gender inequity, catalyzed the conversation.

The Missing 32 Percent project resulted from an incubator event conceived and produced in 2011 by the AIA San Francisco (AIASF) Communications Committee. In turn, Ladies (and Gents) Who Lunch with Architect Barbie was inspired by a partnership between AIA National and Mattel on “Architect Barbie,” whose place on the toy manufacturer’s lineup was insured by Despina Stratigakos and her colleague, architect Kelly Hayes McAlonie. At the event, fellow practitioners Dr. Ila Berman; Cathy Simon, FAIA; Anne M. Torney, AIA; and EB Min, AIA, came together for a provocative panel discussion on the state of women’s participation in the profession, including the impact of “Architect Barbie”.

The popularity of that event fostered the first Missing 32 Percent Symposium on October 12, 2012. A broad range of speakers representing different career paths in the profession ranging from those working for large firms—such as Marianne O'Brien, AIA, and Caroline Kiernat, AIA—as well as sole practitioners and small firms including Anne Fougeron, FAIA, and Eliza Hart, AIA. Panels and breakout sessions highlighted statistics that detail the current leadership structure of architecture firms and discussion on the following: What defines leadership? Who are the leaders within your firms? Who wants to be a leader? And how can men and women work together to increase their value as architects and retain talent in the profession?

The conversation about women's roles in architectural practice coupled with overall challenges for equitable practice and professional satisfaction drove a call to action after the second symposium. The impetus came from the dire need in the profession to go beyond discussion and focus on tangible results to change workplace policy and culture. In July of 2013, less than a month following the second Missing 32 Percent Symposium, an AIASF committee was born from the Building Communication and Negotiation Skills to Fit Your Audience panel (Rosa Sheng, AIA; Saskia Dennis-van Dijl; Trudi Hummel, AIA; and Laurie Dreyer). The charge was to drive additional discussion, research, and publication of best practice guidelines to preserve the profession's best talent.

2014–15: From The Missing 32 Percent to Equity by Design

In early 2014, the group conducted its first national survey on equity in architecture and talent retention. The survey received 2,289 responses from across the United States. The Equity by Design committee hosted its third sold-out symposium, titled Equity by Design: Knowledge, Discussion, Action! on October 18, 2014. In total, 250 attendees traveled from across the United States for the launch of key findings from the Equity in Architecture Survey. They participated in interactive breakout sessions in the three major knowledge areas: hiring and retention, growth and development, and meaning and influence. The group received overwhelming support from firm sponsorship, AIASF, and AIA National as well as positive press coverage including The Wall Street Journal, Architect Magazine, Architectural Record, and Contract Magazine.

In May 2015, during the AIA National Convention in Atlanta, the AIASF committee changed its name from The Missing 32 Percent to Equity by Design to better reflect the mission to address equitable practice for those still in the profession and to expand the outreach of the movement beyond gender. The group designed a half-day workshop as part of the preconvention program: WE310 Equity by Design: Knowledge, Discussion, Action! Hackathon and Happy Hour to expand the awareness and discussion of challenges of talent retention in architecture. A video documenting the EQxD Hackathon by ARCHITECT Magazine highlights the positive reception of the event. The lessons have been captured and shared with a larger audience on this site. The full report of the Equity in Architecture Survey results was issued online on May 13 as a resource to the profession for further the conversation. Concurrently, on May 15, 2015, 4,117 delegates passed Equity in Architecture Resolution 15-1, authored by Rosa Sheng, AIA; Julia Donoho, AIA; and Francis Pitts, FAIA, and cosponsored by the AIASF and American Institute of Architects, California Council, in an overwhelming majority at the AIA National Convention Business Meeting.These events signify a major milestone for equity since the committee's inception. Outreach continued with presentations at TEDxPhiladelphia on June 11, 2015, KQED Forum, and several Keynote opportunities for the duration of 2015.

2016-17: Metrics, Meanings, and Matrices

In 2016, Equity by Design launched the second Equity in Architecture Survey in collaboration with the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. As the largest and most comprehensive study launched nationally to date on the topic of talent retention within architecture, the 2016 survey resulted in analysis of 8,664 completed responses to over 120 questions with the potential to impact architectural practice nationwide and establish a legacy dataset over subsequent years’ studies. Concurrently, the group hosted the fourth sold-out symposium of 250 national attendees with the theme Equity by Design: Metrics, Meaning & Matrices. As a result of strong sponsorship, the group was able to produce an outreach video and the Matrices exhibition, an installation that grew throughout the symposium to encompass highlights of the group’s mission and history as well as symposium highlights as part of the day’s interactive event.

Equity by Design continued to grow nationally and internationally in 2017, and various initiatives expanded upon the research findings with quarterly focus topics, survey metrics, and deep dives on the topics of pay equity, work-life navigation, and ways to affect advocacy through #EQxDActions.

Strategies for Change

In order to make progress beyond the original conversations, the core group (Rosa Sheng, Annelise Pitts, Lilian Asperin, Julia Mandell, and Saskia Dennis van Dijl) determined early on that evolving missions with ambitious goals were key in connecting equitable practice theory to impact design and built outcomes. Additionally, Equity by Design saw the need to build alliances with industry partnerships and expand the umbrella of conversation and participation to the built environment.

The group has adopted a three-pronged approach for implementing change, which includes the following:

Develop knowledge resources through research data and other studies and reference articles to identify challenging topic areas and expose the factors and complexities of each topic area.

Foster discussion, critique, and debate about the research results and various points of view on the challenges from each individual’s background within practice.

Promote action through design thinking on policy and culture changes, skill-building workshops for developing leadership, and initiatives in problem solving.

2018 and Beyond

In marking the five-year anniversary celebrating the group’s work, Equity by Design conducted its third national survey. A national group of volunteers will developed survey goals for capturing career experiences of architectural school graduates from accredited programs (regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, licensure status, or practice status.)

Building upon lessons learned in 2014 and 2016, the survey successfully collected over 14,000 responses from architectural graduates and professionals across the nation. Equity by Design intends to release the key findings of the 2018 survey at #EQxDV: Voices, Values, Vision on November 3, 2018 at the San Francisco Art Institute.